Voting Systems IV – Procedural Voting

This post is part of a series of posts on Voting Systems.

[Edit: I have changed my thinking on this topic following some discussion and further thinking on the subject. I am leaving this post up, but have added a new section changing my conclusion.]

As well as the general public voting for politicians or directly for policies, voting is also used by politicians themselves to decide on issues and pass laws.

Rather than being a “once every few years” phenomenon, this voting is part of the day-to-day workings of government. The standard operating procedure for many politicians.

This means that whilst some sort of formal procedure is needed, even the previously mentioned voting systems of Approval Voting, Score Voting, Evaluative Voting and SPAV are still far to rigid to permit the kind of nuance that is necessary in navigating the complex issues of the day. Rather like using a sledgehammer to crack a nut, too simplistic an approach leads to a broken system. Legislators and governments tend to eventually find ways around a procedure if it is too restrictive, but these loopholes are accidental and therefore do not necessarily yield the best outcomes.

The trouble is, that even using the systems mentioned above, there is insufficient room for the full range of support and opposition to be expressed. Filibusters are a good example of this – they are a way for US politicians to demonstrate extreme opposition to a bill. This action usually comes at a cost, but if a politician feels sufficiently strongly about an issue, they can singlehandedly prevent the bill from passing.

This is obvously far from ideal, as if overused it can prevent anything from getting done. Aside from this however, it is problematic because the cost to the politician is often unclear. Depending on the issue and the views of the other politicians, it could have very little long term impact on the politician, or it could render them a pariah, making people unwilling to work with them.

Pork Barrel Politics is an example from the other end of the spectrum – if a politician doesn’t care one way or another about an issue, their vote is effectively up for sale. Bills can therefore be passed by including within them provisions that sufficiently benefit individual politicians. The cost here is usually borne by the state, again making it a less than ideal situation.

If pork barrel arrangements are able to be banned, this still doesn’t remove the problem, as tyranny of the majority often manifests itself in these kinds of situations, where a large number of people have a very mild preference that is in opposition to a minority’s strong preference. Even using a method such as Score Voting, it costs politicians nothing to vote in line with their mild preference, and without any pork to benefit from there is no reason for them to reduce the power of their vote. This results in them outvoting the minority despite their virtual indifference.

Because voting on issues is a fundamental part of a politician’s job, we can allow for a system of procedural voting that is significantly more complex and nuanced than what we could reasonably expect the electorate to deal with. The effort of understanding the nuances of a system is not really worthwhile if you are only using it once every couple of years, but if you are using it daily, the effort pays off. If we therefore allow ourselves to consider systems that have more complexity, what can we accomplish?

Some people may have read my previous 3 posts, and been wondering why I haven’t mentioned Quadratic Voting yet. In a modern democracy, voting is open to almost everyone in society, so the systems used need to be accessible not just to the average person, but to the vast majority of people. Every additional complication that is added will lose a certain proportion of people, and this contributes to sentiments that a system might be undemocratic (another advantage that approval voting has over ranked methods). Perhaps in some halcyon future, the majority of people will have the time and energy to get comfortable with the nuances of Quadratic Voting, but for now I am not proposing it as a panacea. I am raising it only as a solution to the specific problem of procedural voting, in which the people involved have the resources and incentives to become adequately familiar with it.

Quadratic Voting

The two examples of system loopholes above have something in common – there is a price to be paid for not allowing a sufficient gamut of opinion.

One way to better capture this range of strengths of opinion could be to allow people to forgo their right to vote on one issue in exchange for being able to “vote twice” on another issue. This quite simplistic approach goes too far though – it now makes it too easy for highly motivated minorities to push through legislation. Rather than voting on other important items, politicians could be “free-riders”, relying on other politicians to pass things while saving up their votes to ram through something unpopular.

On the one hand, this allows the system to internalise the costs associated with pork barrel politics, and reduces the need for things like filibusters to allow for strong opposition. The costs become something quantifiable that the politicians themselves bear. On the other hand, this reverses the tyrrany of the majority situation, putting too much power into the hands of highly motivated minority viewpoints. What we need is a system that internalises the costs, but allows for a better balance between minority and majority interests.

Quadratic Voting is a way of doing this that increases the cost of each subsequent vote on a particular issue. This still allows people a wider range of expression than in an ordinary “one person one vote” system, but means that it is not practical for a small minority to completely overwhelm a vote just by abstaining from other decisions.

How it Works

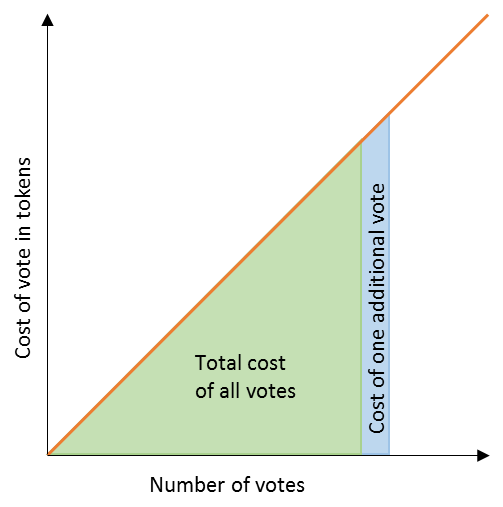

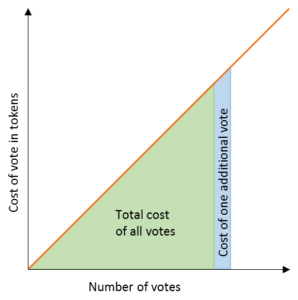

In a situation in which there are multiple issues to vote on, Quadratic Voting provides each voter with a “budget” which can be spent on votes. Voters can vote for, vote against or abstain on any particular issue. The first vote on any particular issue costs 1, as expected, however they can vote a second time on the same issue for an additional cost of 2. A third vote costs 3, and so on.

As a simple example, if there were 10 issues being voted on, and people had 10 votes, they could vote for (or against) each one of the 10 issues. If there were a couple of issues they weren’t particularly invested in either way, they could instead abstain from two, and use those two unused votes to place a second vote on an issue that was particularly close to their heart. In any sensible implementation, it would be useful to distinguish between the numbers of votes themselves and the costs of the votes, so going forwards I will refer to voters as having a budget of “democracy tokens” which are used to “buy” votes. Of course, no actual money is involved, but the concept of “spending” the tokens is a useful one.

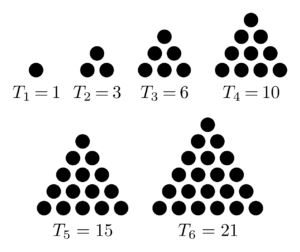

If only one of the 10 issues was one that a particular voter cared about, they could spend all 10 of their tokens buying votes for that particular issue. This would buy a total of 4 votes – 1 token for the first vote, 2 for the second, 3 for the third and 4 tokens for the fourth, for a total of 10 tokens. For those arithmetically inclined, you may notice that this means that buying n votes costs Tn tokens, where Tn is the nth Triangular number. The formula for calculating this is which is where the “quadratic” in the name comes from (in fact this is functionally equivalent to a system where n votes costs n2 tokens, but this is less natural to explain than “the nth vote on the same issue costs n tokens”).

The increasing cost associated with declaring a stronger preference allows some useful results from economics to be applied. As the number of votes on a particular issue increases, the cost per vote increases, meaning that the exact amount that a voter cares about an issue can be found (relative to the other issues being voted on in the same batch). At some point the votes on one issue will become so expensive, that even expressing a mild preference on another issue is so comparatively cheap that it is worthwhile.

Put simply, it allows voters to demonstrate the true value of what a vote on a particular issue is worth to them. A thorough explanation of the principles involved can be found on Vitalik Buterin’s website, which I highly recommend if you are at all interested in the concept.

Implementation

The House of Commons usually has around 200 votes per year (give or take a dozen or so), which generally follow a debate, and can happen on any given day. Unfortunately, many votes don’t have good attendance, often because they are issues that particular politicians are not sufficiently interested in to warrant attending the debate.

Rather than debating then voting, debates could be held during a month and attended by those that are interested, then votes could all occur on a single day at the end of the month – a “voting session” where all are likely to be in attendance. Obviously voting in advance of the session or voting in absentia would need to be permitted to avoid shenanigans (West Wing season 6 episode 17 is a fictional but excellent example of why this is would be necessary).

For every item to be voted on in the voting session, each representative/politician could be given 3 “democracy tokens”. In an average month in the UK’s House of Commons, there would be about 16 issues to vote on, so in this case everyone would receive 48 tokens.

As an aside, 3 tokens per issue is better than 1 which was used in the simple example above. This is because with only 1 token per issue, any additional votes on an issue necessitate that you forfeit an opinion entirely on other issues. With 3 tokens per issue, voters can still express a mild opinion on all votes, even if they want to express a stronger view on some.

Votes being taken in these monthly batches would mean that everyone knows what issues are available to be voted on. This would ensure that no-one spends all their tokens before being aware of an issue they care about more, or equally, save their tokens in anticipation of an issue, only for it not to arise. By extension, this means that people shouldn’t be able to “carry over” tokens from one voting session to the next, as this could result in similar exploitable situations and behaviours.

It would also be important for voting sessions to not be on too few issues, as this would render the benefits of the system irrelevant and reduce it back to fairly ordinary voting. A session with too few issues being raised (perhaps fewer than 8) could be postponed and combined with the next voting session instead.

Within a legislative body, there are a small enough number of people that there is no requirement for voting to decide between individual options. The process of drafting a law could of course include some form of voting with multiple different options as a route towards finding the form of a law that is most likely to pass, but this is not an essential part of the process – such consensus building could rely on the use of sub-committees instead. The final binding votes however can be restricted to whether to pass or reject a specific measure, bill or law. This means that we don’t need to worry about “spoilers” or any potential strategies that complicate votes with more than two options.

It would also be possible to define a threshold, like we did for referenda. Our current system effectively uses a threshold of 0 – a law can theoretically be passed with a majority of 1. To me, this feels too low – if the margin for success is so slim, it is better to stick with the status quo. A 10% threshold would avoid this eventuality but should avoid too much deadlock (allowing new laws to be passed only if they won 55%-45% or above). Perhaps though, a higher threshold would encourage more effort to be made in consensus building.

Either way, with the ability to vote multiple times on an issue, it would be possible for some popular initiatives to achieve support greater than “100%”. This would mean that there were more votes cast for an initiative than there were politicians, but within this system that shouldn’t be an issue. In fact, it would be fairly unlikely, as in a body of politicians if a large enough number support something, they would be aware of the level of support. Therefore, they would be unlikely to waste additional tokens paying for votes when it is almost certain to pass anyway.

Further Reading

As Quadratic Voting is a relatively new idea, it may be useful for me to include some resources giving more information about it. Below are a few links, starting with the original papers proposing the system:

- Glen Weyl & Steven Lalley’s original paper on Quadratic Voting

- Glen Weyl, Vitalik Buterin & Zoë Hitzig’s paper on Liberal Radicalism

- Glen Weyl & Eric Posner’s book “Radical Markets”

- Eric Posner – Quadratic Voting

- Tyler Cowen – Thoughts on Quadratic Voting

- Eric Posner’s response to Tyler Cowen

A few editorials on the idea:

- Vox Article

Spectator Article– this article has been criticised as being misleading- Hackernoon Article

A number of more technical blog posts about the topic:

- Quadratic Payments: A Primer (Vitalik Buterin’s website as above)

- Quadratic Voting with Sortition (Highly relevant to my last post)

- Quadratic voting and types of one person, one vote

- Persistent Voting with Quadratic Voting

[Edit: Unfortunately, despite the ideas above being fairly well publicised, there have been criticisms that they are not quite as original or foolproof as might be being claimed. Firstly, this link section would not be complete without Warren Smith’s analysis of monetised voting systems. This includes something of a polemic against Weyl and Posner’s papers and claims.

Problems

Taking Warren Smith’s comments into account, this system looks a lot less attractive, and opens up whole new cans of worms that must be reckoned with.

Monetised voting systems introduce the possibility that politicians could introduce “spam” bills. These would be easy to make threatening to a minority, forcing their opponents to waste tokens voting them down. This would then prevent the minority from being able to pass any of their desired legislation.

The lack of constraints on bills that could be introduced to a legislature makes the scope of this problem quite serious. There may be many other areas in which exploits could be found in this new, untested system.

Whilst it may be possible to find a use for monetised voting systems for very well constrained problems such as budget allocation, it is something of a solution in search of a problem. Indeed, if you’re looking for a way to bring the power of markets to voting, Robin Hanson’s Futarchy proposal is possibly a better place to start. At least betting markets are already an established and understood mechanism.

Per the previous posts, if some movement were successful in driving the introduction of Approval Voting for electing leaders, this would likely lead to less divisive politics and easier compromise. The further reform of selecting representatives using partitioned sortition would reduce their incentives to grandstand and obstruct. At this point, the issues raised above whilst not completely avoidable, are likely to be much less pathological, and more like occasional minor annoyances.

At this point, procedural voting would probably best be done using the same method as for referenda – Evaluative Voting with a sensible threshold. It is likely that a lower threshold than what is used for referenda would be helpful to avoid legislative paralysis, after all, there would be far more frequent procedural votes than there would be referenda. As can be seen from the situation in the US arising from the threat of a filibuster, forcing all legislation to require a supermajority before it can be passed is not a particularly efficient way of running a government.

Of course, different thresholds could be used depending on the subject matter of the vote – “constitutional” matters should require a higher bar of approval before the status quo can be changed. That said, ordinary votes should probably use a threshold of 2% to 10% of the total possible score. The easier it is for a government to pass something, the easier it is for a government to reverse it too.

Further to this, Evaluative Voting allows multiple versions of legislation to be considered simultaneously, removing the necessity for sub-committees, and facilitating consensus building. Of course, sub-committees may still have a place in drafting and in curating the alternatives, but being able to simultaneously vote on multiple versions of a bill could overcome a significant amount of deadlock.]

Conclusion

The right voting method needs to be used for the right purpose. In the first of these four posts, I identified 4 different situations in which voting is used, each of which has very different requirements. Having considered each in turn, the following methods currently look the most promising in each situation:

- Leaders (Presidential/Gubernatorial Systems)

- Approval Voting is a very simple method to use and to implement that avoids all of the most egregious pathologies that plague voting methods

- Alternatively, Score Voting could be used if people were receptive to the slightly higher complexity

- Either Approval or Score voting could be supplemented with a (non-automatic) top-two run-off vote, however a second vote adds expense, and turn-out in run-off elections tends to be lower than the initial vote

- If a run-off was desired however, this would have to be as a separate election, as any kind of automatic run-off introduces pathological behaviour that negates many of the advantages that Approval and Score Voting provide

- Even under a parliamentary system, a leader still needs to be elected by the parliament, and it would still be sensible for them to use Approval or Score Voting for this purpose

- Referenda (Direct Democracy)

- Evaluative Voting (Score Voting with the range {-1, 0, 1}) allows for the level of support for a range of possible motions to be accurately ascertained, allowing votes against to be qualitatively different to abstentions

- A threshold between 10% and 50% of the total possible score would ensure that laws wouldn’t change with a knife-edge majority

- This system would remove the discontinuity caused by turn-out thresholds, removing the argument that people should abstain rather than vote against an issue they disagree with

- Representatives (Representative Democracy/Parliamentary Systems)

- Partitioned Sortition, whilst not strictly a voting method, allows for the selection of representatives in a way that virtually guarantees proportionality, as well as avoiding populism, misleading campaigns or relying on a political class

- The partitions can be overlaid on top of one another without reducing “constituencies” to tiny groups that are too small to be represented, in fact the partitions can ensure that even fairly small groups of people are able to be appropriately represented

- If sortition is not politically possible, then Sequential Proportional Approval Voting is a good method to generate a proportional body of representatives

- Procedures (Intra-governmental decision making)

Quadratic voting allows a greater range of opinion to be expressed, when people are going to be voting on a large number of things in a similar timeframeIt internalises some costs that have previously been borne by the society at largeIf the representatives were selected by sortition, it would be these people that would be using Quadratic Voting every month to decide on what to pass- As with referenda, Evaluative Voting is likely to improve consensus building, and permit more fluid political alliances than current de-facto two-party systems

- A threshold between 2% and 10% of the total possible score should allow things to be passed without too much legislative paralysis

- With leaders and representatives elected using the methods above, many issues arising from “political capital” are likely to be less prevalent

Of course, it is important not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Electoral reform takes time, and the current Plurality/First Past The Post system used in the UK and US is one of the worst ways to do it of all. With that in mind, I welcome the recent initiatives that are seeking to move us away from FPTP, even if they might not be advocating my preferred method. The more things change, the more open to change people become. Therefore, even if the change is only a minor improvement, and isn’t to the system that is the best, it can encourage further more rapid change later on.

One Reply to “Voting Systems IV – Procedural Voting”